As Anti-Bias Educators, one thing we should be reflecting on is the role that place plays in our history, culture, and orientation to the world. All land carries stories, and if we think about story as being rooted in place, we can begin to be more inclusive in our learning and teaching of all disciplines. Our children, if taught to use their local community and environment as a source of knowledge for learning, will strengthen bonds with their communities, have a stronger appreciation for the natural world, and be more likely to become committed activists.

As Anti-Bias Educators, one thing we should be reflecting on is the role that place plays in our history, culture, and orientation to the world. All land carries stories, and if we think about story as being rooted in place, we can begin to be more inclusive in our learning and teaching of all disciplines. Our children, if taught to use their local community and environment as a source of knowledge for learning, will strengthen bonds with their communities, have a stronger appreciation for the natural world, and be more likely to become committed activists.

Our AMAZEworks office sits in Lowertown St. Paul, along the Mississippi River, or Wakpá Tháŋka in Dakota. This is Dakota homeland. Sacred sites, such as Eháŋna Wičháhapi (burial mounds at Indian Mounds Park), Wakháŋ Thípi (Carver’s Cave), and the village of Kap’óža surround us. We are just downriver from Bdoté, the place where two rivers meet and most importantly, the center of Dakota spirituality and history. It is important for us to recognize that unless we are indigenous Dakota, we are on stolen land, taken through an unauthorized and illegitimate “treaty” in 1805. We recognize the acts of genocide committed against Native people. And perhaps most importantly, we acknowledge that indigenous people are still here and present all around us. To the indigenous members of my community – your voices deserve to be elevated.

On Indigenous Peoples’ Day, October 14, 2019, I attended an event at Metro State University hosted by the Native Governance Center and Lower Phalen Creek Project to learn more about Indigenous land acknowledgment. The panel discussion of Native elders, professionals, and youth included

Land acknowledgment is rooted in indigenous practices. Indigenous land acknowledgment has become increasingly popular in recent years, even though the U.S. continues to be way behind other countries like Australia and Canada. I wanted to learn more about how we can not only acknowledge indigenous land but also indigenous people. This event deepened my own understanding of how land acknowledgment can be a part of how indigenous people and colonizers work together toward decolonization.

The panelists talked about their own experiences with land acknowledgments, important considerations and things to reflect on, and how indigenous land acknowledgment is one way to speak truth to power but needs to be backed up by action in order to be authentic. Following the event, the Native Governance Center published this Guide to indigenous Land Acknowledgment on their webpage. It offers information about why indigenous land acknowledgment is important along with tips and things to consider when giving an indigenous land acknowledgment statement. I also came across this article, What to consider when acknowledging you are on stolen indigenous lands, on the Healing Minnesota Stories blog, which talks gives more information about the event and includes some of the most powerful quotes of the evening.

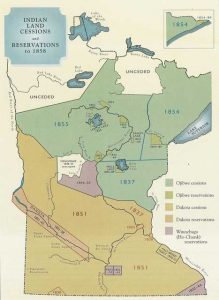

Something that struck me as an educator, is what panelist Kate Beane said about how we need to “acknowledge the past in a way that empowers young people.” One way we can do this is to incorporate language whenever we can, continue to learn about this history of place, and to make sure our acknowledgments include a celebration of indigenous communities. One resource I’ve found is the Dakota Land Maps by artist Marlena Myles (Spirit Lake Dakota, Mohegan, Muscogee). The website also includes a list of important Dakota place names in the Twin Cities along with pronunciations. Many other resources published by or in partnership with Native people exist, and I encourage you to find them for your area.

At AMAZEworks, we provide tools and curricula for educators to regularly facilitate conversations around identity, difference, and bias that encompass a variety of identities and lived experiences, including Indigenous/Native American. One way we try to honor Native voices and experiences beyond just land acknowledgment is through books and lessons in both our elementary and secondary curricula. We work with a variety of people across identities and lived experiences to make sure the books, videos, and lesson materials are accurate and do not depict Native people in stereotypical ways. We also provide trainings and work with schools to help develop and support teachers as anti-bias educators. Through Anti-bias Education and constant learning/reflection, we hope to empower young people.

We can acknowledge the indigenous people in our communities and let others know how we can work together locally to take action against injustice. Land acknowledgment should include all of these things and be a step toward land return. Land acknowledgment should leave indigenous people encouraged and strong. We encourage you to start with learning and reflection alongside land acknowledgment but to continue with support and a commitment to making change.

Map Credit

Source: https://www.mnopedia.org/multimedia/native-american-land-cessions-and-reservations-1858

Description: Map of Native American Land Cessions and Reservations to 1858. In “Territorial Imperative: How Minnesota Became the 32nd State,” by Rhoda Gilman (Making Minnesota Territory 1849-1858; Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1999)