Sydney Carlson knows the power of regular, intentional conversations about racial identity and difference. In 2016, Sydney worked at J.J. Hill Montessori Magnet School in St. Paul, Minnesota. When Philando Castile, the school’s nutrition services supervisor, was a victim of police brutality, she mourned his life alongside her school community. She observed and participated in open discussions among students and adults across racial identities about the tragedy. The community came together to remember Castile’s life and impact on the school.

After George Floyd’s murder in 2020, Sydney saw a different response in her school community. She then worked at an elementary summer program in Minnetonka Public Schools and was the only Black person on the staff at her school among mostly White students. “I heard nothing about George Floyd’s murder,” she said. Despite being only twenty minutes from the sight of Floyd’s death, an event that garnered international attention and calls for racial justice, Sydney’s community was silent, seeing themselves as unaffected by the news.

Sydney felt like if she didn’t take action, no one would. She did not want her White students and colleagues thinking systemic racism didn’t impact them. She wanted to create a change and give children a resource to have conversations about race and antiracism. She asked herself, “How can I share this message with people who are growing up with power and resources? How can they know what they are unaware of? How can I help to make them aware?”

Sydney wrote a pledge. The pledge became a daily mindfulness practice in her classroom, carving time for students to reflect on race and racism and commit to action. “I didn’t want to write about race from the perspective of a Black person,” Sydney said. She wanted White children to have the tools to talk about race and recognize their power and responsibility. She wrote it for White students to see themselves as crucial to the work of racial justice. “In many ways [they] have more power than kids in other groups and need to use that power responsibly,” she said. The White community was impacted, whether they knew it or not.

As a daily exercise, the pledge used repetition as a learning tool. Each day, it resonated more with students, allowing them to engage deeply with the material and ask hard questions. The pledge resisted colorblind racism and prepared children to have their understanding of the world challenged. It provided White students with ways they could live antiracist lives.

After Sydney started leading the pledge in her classroom, she saw a change. Her students knew who George Floyd was and talked about him in the classroom. They asked questions about race and racism. They saw themselves as agents of change. “They were able to handle the information many of the adults in their immediate community felt was above their understanding,” Sydney shared. When providing students with real-life examples of racial injustice, shared language, and the space to ask questions, Sydney found that her students wanted to lead antiracist lives.

Quickly, thanks in large part to her educator mother, the pledge expanded outside her classroom. Teachers and parents asked for copies to bring into their classrooms and homes. One of her students wrote down the pledge to take home. There was demand for the resource, and Sydney wanted to make it more accessible.

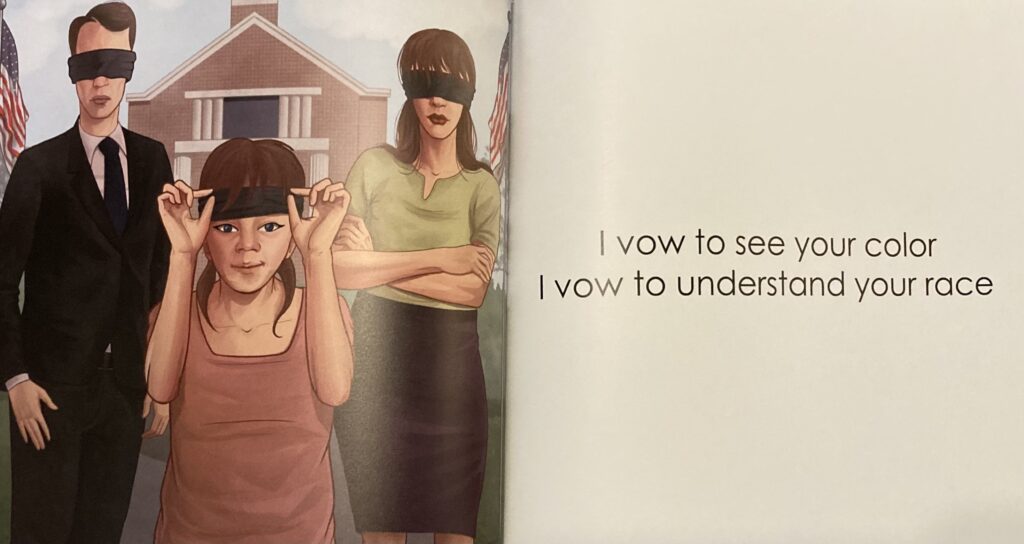

She adapted the pledge into a children’s book, Racism STOPS with Me: A Pledge of Intention for Elementary School Children and their Adult Leaders. She added introductory sections and reflection questions to spark discussion with kids. The illustrations, a product of Malawi illustrator Saidi Alifa, fostered further engagement and participation as students could physically see themselves represented in the book.

Kids notice differences. Talking about these differences helps us counter our biases and create cultures of belonging for all. There is power in regular, intentional conversations about identity, difference, and bias. People of all identities and lived experiences need to participate in those conversations to help create communities of belonging.

Sydney understands that we all play a vital role in bringing belonging to life. That’s why she chose to focus on White students in her pledge. Even though years have passed since Floyd’s tragic murder, the persistence of racism and police brutality continues, which is why it is essential for us to continue our commitment to antiracism. Consider a reflection question at the end of Sydney’s book: How do you make a vow to end racism today? This question carries the hope that each of us can make a difference and contribute to a future where everyone belongs.

P.S. Next month, AmazeWorks is launching our Books for Belonging campaign for Give to the Max. Nationwide, books and stories are being stripped from classrooms, depriving children from having important conversations about identity, difference, and bias.

We know that books bring belonging to life. AmazeWorks is committed to bringing those books into schools. Give to the Max season starts on November 1, but if you give today, we will count your gift for the Books for Belonging campaign.