Despite systemic denial and minimizing across the world, decades of statistics support the harsh realities of climate change and its catastrophic effects. Since the Industrial Revolution, human-produced greenhouse gas emissions have increased, causing the Earth to warm and its climate to change drastically. Experts predict severe consequences due to climate change. These effects will diminish Earth’s habitability, as they continue to increase the frequency and severity of natural disasters such as sea-level rise, increased flooding, and drought. Despite the universal impact of climate change, each community will be affected differently. Climate change already has and will continue to exacerbate the systemic inequalities in our society.

Despite systemic denial and minimizing across the world, decades of statistics support the harsh realities of climate change and its catastrophic effects. Since the Industrial Revolution, human-produced greenhouse gas emissions have increased, causing the Earth to warm and its climate to change drastically. Experts predict severe consequences due to climate change. These effects will diminish Earth’s habitability, as they continue to increase the frequency and severity of natural disasters such as sea-level rise, increased flooding, and drought. Despite the universal impact of climate change, each community will be affected differently. Climate change already has and will continue to exacerbate the systemic inequalities in our society.

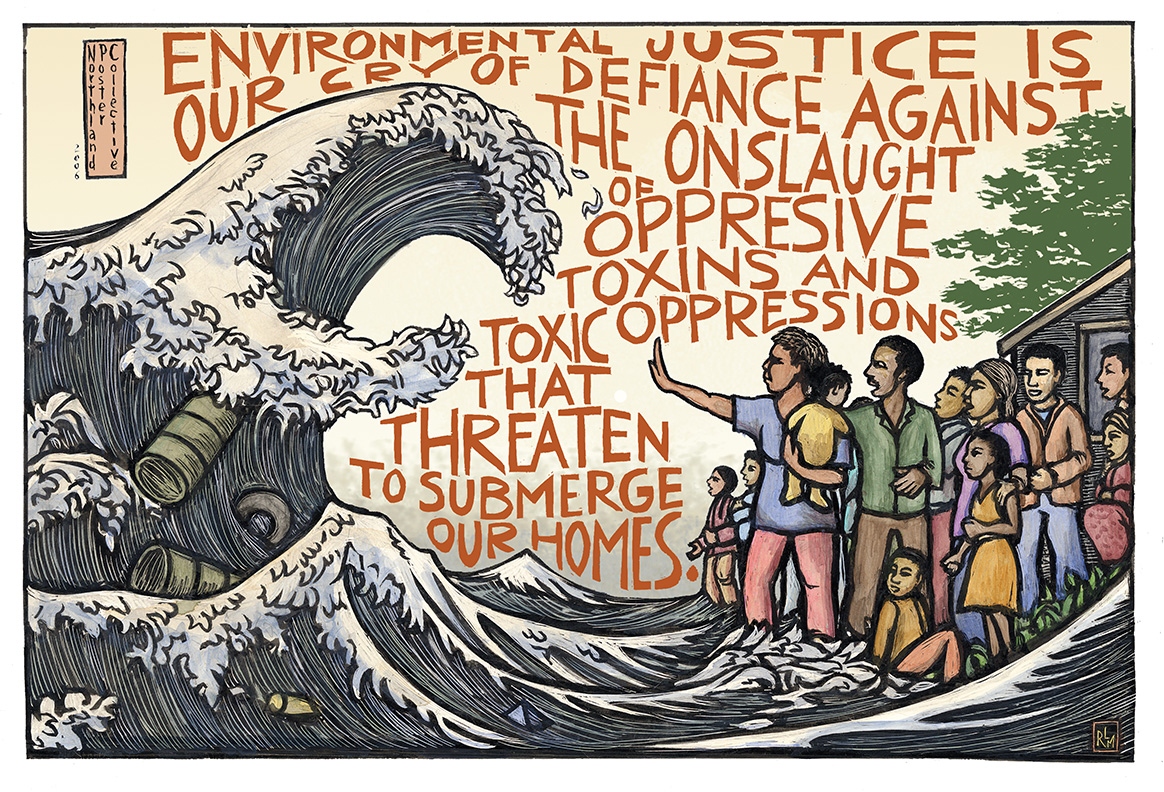

The environmental justice movement exists at the intersection of racial justice and environmental activism. Movement leaders define environmental racism as the disproportionate harmful exposure and impact of environmental hazards on Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

In the 1980s, North Carolina state officials devised a plan to dump toxic waste in Warren County. The majority of people living in Warren County were Black and of lower socioeconomic status, a demographic group not reflected in other counties. The community organized against the state dumping toxic waste in the nearby landfill. Though this community lost this specific battle, their powerful efforts thrust the environmental justice movement into the public eye and garnered national attention. The prominence of their struggle helped empower other BIPOC communities fighting against environmental racism to share their stories. The resulting community is still advocating systemic change to combat environmental racism, which becomes more salient every day that climate change is not addressed.

Along with decades of recorded lived experiences, numerous research projects have provided quantitative data which support the need to address these struggles. In 1987, the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice published a groundbreaking study on environmental racism. Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States found that a community’s racial makeup is the number one predictor of toxic waste facility locations. A 2019 study found that Black and Hispanic communities are exposed to more air pollution than they produce. By contrast, White people disproportionately cause air pollution while they do not live in polluted areas. Air pollution has been linked to health problems such as decreased lung function, aggravation of asthma, and increased respiratory issues.

Each of these issues is further exacerbated by COVID-19. In 2020, Harvard University published a study that found long-term exposure to air pollution is linked to a higher COVID-19 death rate. Therefore, BIPOC populations living in areas with lower air quality are at higher risk of dying from COVID-19 than White people who experience higher air quality. This recent circumstance is one example of how racist environmental frameworks harm BIPOC communities. It reifies the need to follow the guidance of intersectional activists, such as environmental justice movement workers.

There are also racial disparities in climate activism and response, which parallel the trends in impact. Yale University’s 2019 Program on Climate Change Communication survey found that 69% of Hispanic/Latinx respondents and 57% of Black/African American respondents reported they were Alarmed or Concerned about global warming. By contrast, fewer than 50% of White respondents were Alarmed or Concerned about global warming. This theme was further supported when the conversation turned from concern to action. In response to another question, 37% of Hispanic/Latinx respondents and 36% of Black/African American respondents said they were willing to “join a campaign to conceive elected officials to take action to reduce global warming.” In parallel with previous responses about climate concern, notably fewer White respondents said they were willing to join a campaign, with just 22% of respondents. This study’s raw data alone do not inherently result in statistically significant conclusions. Despite this need for further analysis, the data does suggest a compelling theory: that BIPOC communities are likely to care more about climate change than White communities. With the previous knowledge in mind, it could follow that this activism is a direct result of marginalized racial groups’ disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards, such as air pollution.

Per Teen Vogue’s 2019 article, many young climate activists are striving towards justice for people and the planet. They are ready to tackle this daunting issue at full force. Younger generations are working to diversify the environmental justice movement, in order to reform the problematic history of White men and women dominating mainstream environmentalism. A 2019 Washington Post-Kaiser Family Foundation Poll found that “[the] majority of teens feel afraid and angry about climate change, but also motivated.” The poll results also delineated that twice as many Black and Hispanic/Latinx teenagers were involved in school climate change events when compared to White teenagers. The poll offers a hopeful glimpse of what the future of the environmental justice movement could look like: a more racially diverse and inclusive community that more accurately represents the populations most affected.

As we consider what it means to embrace change, it is important to know what roles we can play as Anti-Bias allies, educators, or caregivers. Anti-Bias Education emphasizes to children and youth that everyone has the same rights: to clean air and water, access to fresh food, affordable transportation, and housing, and access to green spaces. We are lucky that young people have chosen to get involved to reform the historically biased community of climate change activists and embrace the intersectionality of the environmental justice movement. As we move forward, it is important to be intentional about promoting an Anti-Bias mindset as it applies to environmental justice, so the next generation is equipped to follow in these revolutionary footsteps. One way to do this is through sharing stories that provide windows into the lives of people experiencing environmental racism, alongside stories with mirrors that reflect children’s own lives. Additionally, having honest conversations with children and youth about the environmental inequality that communities of color face will teach them to value each others’ complex identities, respect each others’ differences, and treat each other with empathy.

Sources:

Image credit: Ricardo Levins Morales