“Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. This goal will be achieved when everyone enjoys:

“Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. This goal will be achieved when everyone enjoys:

-EPA (https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice)

“WE, THE PEOPLE OF COLOR, gathered together at this multinational People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit, to begin to build a national and international movement of all peoples of color to fight the destruction and taking of our lands and communities, do hereby re-establish our spiritual interdependence to the sacredness of our Mother Earth; to respect and celebrate each of our cultures, languages and beliefs about the natural world and our roles in healing ourselves; to ensure environmental justice; to promote economic alternatives which would contribute to the development of environmentally safe livelihoods; and, to secure our political, economic and cultural liberation that has been denied for over 500 years of colonization and oppression, resulting in the poisoning of our communities and land and the genocide of our peoples, do affirm and adopt these Principles of Environmental Justice…”

– Principles of Environmental Justice

I was in college the first time I ever heard of the term environmental justice. I did an environmental justice summer institute at Tufts University near Boston, working as an intern for Save the Harbor/Save the Bay, a small nonprofit focused on cleaning up and protecting Boston Harbor and the surrounding marine environment. I supervised a group of youth leaders, who gave presentations to community groups that were directly affected by pollution and environmental degradation, educating them on this issue and providing resources to empower them to advocate for change.

It was during this time that I learned about NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard), the phenomenon in which people want services and industries that make their communities better and more convenient (new landfill, recycling center, water treatment plant, etc.) as long as they don’t have to see it, hear it, or smell it in their own neighborhoods. Unfortunately, the people with the fewest resources and least amount of power and agency in society, often people of color, indigenous people, immigrants, and people living in poverty, are the most negatively impacted by both environmental degradation and pollution as well as the NIMBY efforts to address these issues. Just look at some of the more infamous examples of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Erin Brockovich, Flint, MI, and the Enbridge Line 3 and Dakota Access pipelines.

More and more, the environmental justice movement centers around righting the wrongs of environmental racism – the disproportionate negative effects of environmental hazards on people of color/indigenous people. Think about: In whose neighborhoods and communities are toxic wastes dumped, railroads, highways, and oil pipelines constructed, industrial complexes built? Who are the first people pushed out by beautification and clean-up efforts along riverfronts, warehouse districts, and downtowns?

Environmental justice advocates and activists call into question the EPA’s definition of environmental justice because it does not directly address or provide a call to action for redressing environmental racism and the systems of oppression that serve to create the problems in the first place. And of course, we must now look at the larger impacts of climate change and think about environmental justice on a global scale.

So what is the connection between environmental justice/climate justice and anti-bias education? When we teach children to respect each other’s complex identities and appreciate each other’s differences, and to notice, name, and reject bias-based mistreatment of others, we are teaching them to see each other’s humanity. When we see each other’s humanity, we see our grandmother in the Inuit elder in Kivalina, Alaska who will lose her island home in the coming years due to rising sea levels, and our child in the African American teenager in Pittsburgh who has severe asthma because he lives near U.S. Steel’s Clairton Coke Works plant, the biggest source of air pollution in the U.S, and our sister in the 42-year-old woman who died of cancer due to pollution from nearby petrochemical plants in Louisiana.

Anti-bias education teaches our children to see each other and each person as worthy of a world in which clean air, clean water, clean energy, and clean food are human rights deserved by all of us. It teaches them to SEE the racial, cultural, and socioeconomic bias inherent in our decisions about city planning, resource distribution, clean-up efforts, and how/why we decide in whose backyard the toxic waste dump gets built. Because when we BELONG to each other, we look to repair the harm done to the most vulnerable among us and advocate for NIABY (Not In ANYONE’s Back Yard) instead of NIMBY.

For more information:

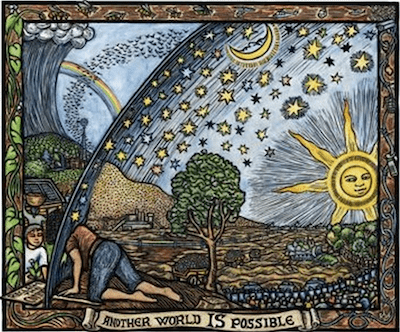

Quote & Image by Ricardo Levins Morales:

“Another World IS Possible! A vision of change, with art based on the nineteenth century Flammarian engraving. One side of the image shows strip mining, deforestation and police/military repression. The other depicts a healthy ecosystem, sustainable energy, and cooperation.”