Identity matters.

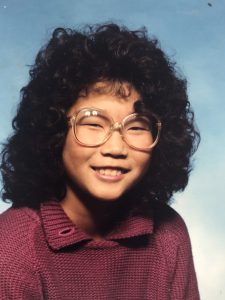

I came of age in the 80s and 90s when Meg Ryan  was one of the biggest romantic comedy stars. As an adolescent, all I wanted was to look like her with her blonde curly hair and piercing blue eyes. In 7th grade, I took a picture from her movie, When Harry Met Sally, to the salon to get a perm. I never did end up looking like Meg Ryan.

was one of the biggest romantic comedy stars. As an adolescent, all I wanted was to look like her with her blonde curly hair and piercing blue eyes. In 7th grade, I took a picture from her movie, When Harry Met Sally, to the salon to get a perm. I never did end up looking like Meg Ryan.

For me as a Korean American adoptee growing up in a white family in white middle-class suburban communities, all I wanted was to be white, preferably with blonde hair and blue eyes. And I rejected the few popular images of Asians in the media at the time, mainly Bruce Lee and Connie Chung, a Chinese American newswoman who was the only Asian American female “celebrity” that I was aware of.

School didn’t help either. My understanding of Asian anything came from country studies units in grade school during which I got very good at drawing the Korean flag and finding South Korea on a globe. Asian topics seemed foreign/exotic, far away, and relegated to the past. U.S. history included Asian immigrants and Asian Americans as mere footnotes – the gold rush, transcontinental railroad, Chinese Exclusion Act, Japanese American internment camps, and maybe the Vietnam War. Nothing at all about the everyday contributions of Asian Americans, and definitely nothing about Korean Americans specifically because “No, I’m not Japanese” and “No, I don’t speak Chinese.”

Of course, my story is not unique. Millions of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) children have grown up in America and have been educated in American schools having their histories and cultures stereotyped, made invisible, erased, or outright lied about.

When I became a middle school social studies teacher almost 20 years ago, I wanted to be the teacher that uplifted and honored the histories, perspectives, and voices of children like me, who lived their lives in relation to a dominant narrative that never included them.

Fast forward to the spring of 2017 when I learned a very valuable lesson about identity and the power of narrative. I was teaching my 7th and 8th graders about Black Lives Matter in the wake of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, and so many others. My intent was to help my non-black students understand that the struggle for freedom and justice for Black and African Americans is not over and that racism and white supremacy live in our systems and institutions and not just in the past, or in white KKK robes, or in the deep south.

I showed my class a series of New York Times videos, entitled “A Conversation on Race”, which included videos on police officers talking about race and racism, black parents talking to their black sons, and black male youth talking about growing up black in America. Very powerful videos, each offering a different perspective and hopefully building empathy and understanding in my students.

But I was so focused on teaching my majority non-Black students about racial justice for black and brown people in our country that I failed to recognize the harm I was doing to the two black students (I’ll call them Sasha and Deshawn) who were in my class. In my pursuit of a social justice education for the majority, I did not consider or even see the identities of the few. And I did not consider the spirit-killing power that the narrative of Black and African Americans as oppressed people would have on Sasha and Deshawn.

After we watched the video of black male youth sharing their fears, frustrations, and experiences with racism, I looked back at my class and saw DeShawn with his head down, hoodie hiding his face, clearly trying to disappear, and Sasha in tears, as she later told me, she thought about her dad and younger brother and fearing for their lives in a way that she hadn’t considered before.

And my heart dropped into my stomach. Here I was perpetuating more harm on the very students whose experiences I was trying to amplify. By crafting my lesson for the racial majority in my classroom, even though I thought I was being responsive to current events and helping students talk about issues that many teachers shy away from, I failed to truly see and value the black racial identities of Sasha and Deshawn and consider the impact of those videos and their peers’ reactions to them.

Identity matters.

We must always consider: How do our identities bias our choices about what perspectives, stories, and frames of reference we choose to highlight and share? How do our identities bias which student identities and narratives we choose to see, affirm, value, give voice to, deny, dismiss, or erase?

The white racial identities of my elementary school teachers biased their choices about what and how to teach so that my Asian American identity was essentially erased in school. In teaching the Black Lives Matter unit, I failed to consider how my own racial identity as a non-Black teacher of color showed up. Because I am not white and had experienced racism in my life, I felt such an urgency in teaching my white students about race and racism. But my experience with racism as an Asian American woman is not akin to what Black and African Americans live through on a daily basis. And though I wouldn’t have admitted it at the time, I realize now that, in some ways, I felt I was justified in trying to speak for Black lives because I was a person of color, too. I know now that I needed to do much more of my own self-reflective work so that I didn’t put my own agenda on my students.

Today, I no longer teach adolescents. Instead, I teach adults how to be anti-bias educators. Through AMAZEworks, I teach teachers to develop an anti-bias mindset and engage in ongoing self-reflection about how their own identities and biases impact their relationships with children and families, their classrooms, and their teaching practices. Anti-bias education helps us examine ourselves as educators while also centering the narratives, identities, and perspectives of our students.

Anti-bias education teaches us that identity matters. I have focused today on racial identity in particular, but identity matters across all differences, including class, culture, gender diversity, ability, beliefs, sexual orientation, and other social identities.

At AMAZEworks, we use Anti-bias education as a model for helping teachers reduce bias levels in both children and themselves by navigating conversations with children of all ages on identity, difference, and bias. Our anti-bias elementary curriculum uses picture books, and our secondary curriculum uses short videos to prompt these discussions. These books and videos provide mirrors so children can see themselves reflected in the curriculum and windows into the lives of others who are different from them. Through these conversations, children learn to name, notice, and reject identity-based bias in all its forms.

So how can you learn to be an anti-bias educator? To begin with, start asking yourself:

We know that identity matters. Students make meaning of themselves in our classrooms. I carry Sasha and Deshawn with me every day as I do this anti-bias education work, and I wonder what impact I had on how they saw themselves and how they constructed their own narratives about who they are and, more importantly, who they could be in the world. And if only I could have had an anti-bias educator as a teacher growing up, so I could have learned at a much earlier age that my own identity matters as much as Meg Ryan’s.